Minato no Hoshizora: Part 1

Without warning, the world turned white.

In a violent rush the light struck the boy's eyelids, as powerful as a blow. Blinding, even with his eyes closed.

How bright, he thought. What could it be?

Both his mind and body felt light, aloof.

Where had this light come from? As he began to think on this, the boy came upon a more pertinent question.

Where was he?

And who, he thought, am I?

The boy was beset by confusion, adrift without a handhold in an ocean of light.

Timidly, he eased his eyes open.

His breath rushed out in awe. Before his eyes, blindingly bright, shooting stars were falling. The window by his bed welled with light as the stars fell, endlessly, brilliant bright lines arcing across the night sky.

His eyes couldn't bear the brightness any longer and he shut them again tight.

Was he dreaming, he wondered, or were these meteors real? And who was he, who did not know even his own name?

And as he wondered, the shapeless fog that had filled his mind began to thin. Ah….

Yes. Now he knew. Recollection was emerging out of the fog – recollection, or indeed, reawakening. His consciousness was reasserting itself.

My name is… Minato, he thought. Nine years old. This is a hospital room. I've always been here. How could I have forgotten something so obvious?

He suddenly felt that he'd be able to stand the brightness now, after all, and he forced his eyes open. But what had he expected to see? The walls of the ward room greeted him, the same, familiar walls, the only place he'd ever known. The hospital sheets beneath him crinkled softly. At the foot of his bed was a TV, powered off. The ceiling above him was grey, the embedded light undecorated and utilitarian. It had been set to night-light, and the room was currently suffused with a gentle orange glow.

Minato climbed down from the bed. Reaching the window, he placed his hands against the glass and looked upwards at the sky. He caught sight of a faint figure in the glass, slim and with hair that, for a boy, was long.

But the focus of his gaze was on a single brilliant point in the night sky, from which streamed out streaks, lines, rays of light, to come to fall one by one upon the Earth. As he gazed at it, transfixed, he almost forgot about the world. For an instant, all he knew was him, and the shooting stars falling.

Was he dreaming? he wondered. There wasn't a meteor shower listed for tonight on the almanac and in any case, such a literal shower of light was a physical impossibility. And the dosage of his pills had been measured so that he would not find himself waking at night.

Slowly, the light began to weaken, and at last it faded away entirely.

The view from the window began to take on its usual looks. The distant hills lay in their low, blackened line, and, high above them, the stars began to shine in the sky again. Now he could see Aldebaran right against the upper frame of the window, the red eye of Taurus. And also there, next to the V that formed the head of the Ox, nestled the Pleiades like gemstones in black cloth.

But this was odd, though. He’d spent his whole life in the hospital: where, then, had he found the time to learn what he knew about the stars? He turned the thought over and over in his head, feeling like he was straining to reach for some kind of understanding, until finally the answer blurred into definition before his eyes. What is wrong with me, he wondered bemusedly, giving his head a good shake to clear it. Of course he knew about the stars. He might not have been able to go to school, but he'd certainly kept up with his studies. What had happened to him to make him forget all this?

Maybe shaking his head had helped, for clarity was returning to his thoughts.

Remember. He loved astronomy, had a complete star chart pinned up on the wall, astronomy books and a small telescope in his bedside cabinet, and even a mini-planetarium projector his father had brought him. His name, too, had come from the stars. Of course he knew his stars.

And now, like at a scene of dominoes where the tape is reversed and each tile rises after its successor in an unbroken sequence, his memories were returning.

He could remember Miss Fujiwara teasing him about being too spoiled for his own good. That had been right before he’d gone to bed. Before Miss Fujiwara had been dinnertime, where as usual he’d not managed to finish more than half of the meal. Before dinnertime, he could remember his mother’s sad-looking face as she’d said goodbye for the evening. Before that, his afternoon IV drip, and before that? The tasteless lunch that he’d forced down, Dr. Eguchi’s turn on today’s mid-morning check, watching a TV show on eighth grade science at ten o’clock, his breakfast of a slice of toast.

Was the homogeneity of his everyday life turning his brain into mush?

The boy laughed softly at the image, but his laughter soon petered out. The grim reality that he'd never be able to leave this hospital he'd been in all his life loomed over his thoughts, and drew the laughter from him into a sigh.

Slowly, he raised his head to look once more out of his window.

What had been the light just now? It was too bright to be a meteor shower. It felt almost as if it'd given his stagnant existence a shape and definite dimension. As if he’d been sinking into an ocean of darkness and the light had impressed him with a lithographic flash upon reality: as if he’d been buried in heavy, unmoving mud and earth and it had lifted him out into the free air.

As if the light had come to seek him out, here in the lonely hospital room forgotten by the rest of the world.

Minato was not actually sure why he had to be hospitalised. His impression was that he was in fairly good health – but that was, in fact, simply because he was only ever conscious when his health had taken a turn for the better. Meaning that although the nurses would always bestow their pity on him for “spending all his time asleep”, he had no such recollection – as far as he knew, if he was indeed spending his time in bed it was either reading or playing videogames.

His parents always came by to visit just when he was beginning to feel lonely, as though they had Minato-loneliness radars built into them. Despite being extremely busy people, they never failed to behave like model parents in paying attention to their sick son. His mother would drop by even on her way to meetings just to pat his head and give him a quick kiss on the cheeks, and to say, sadly, that she only wished she was able to visit him more. His father would come whenever he had days off and ask him, with a clumsy sincerity, Are there any books you want? Anything you’d like to eat?

The doctors, too, came often. There were so many of them he could barely remember their faces, and the only one that he could remember clearly and liked the best was Dr. Eguchi, who wore glasses, had a soothing voice, and always wore a wide smile. Whenever he listened to Minato's heartbeat, he'd always put his own hands over the stethoscope’s probe first, to warm it beforehand.

There were also many nurses, all of them very kind and not a little unlike a bunch of older sisters. Minato especially liked Miss Fujiwara, a rather fashionable and young nurse with dyed chestnut-brown hair, who always seemed to have some mascot character peeking out of a front pocket on the top of a pen. Whenever Minato showed the inclination for conversation she would always be happy to bite and sit down for a chat with him. She was often praising his parents for being so doting. “Normal kids don't get to watch a lot of TV,” she’d say, “but you on the other hand are allowed to watch it anytime you want so you can keep up with your studies. Well, it's not like manga[1] or variety shows are all that educational, so it's just as well that you prefer learning shows and documentaries, isn't it? Maybe you don't know this, but your parents have been reading you books while you were asleep! Stimulation for the brain, to make up for you not going to school. Aren’t there cases where people suddenly find themselves knowing things they hadn’t ever learnt? It’s all because of sleep learning, I personally think. Sure, it’s not scientifically proven, but I believe it. I couldnt not believe it after hearing all the grown up words you use!”

One of Minato’s memories of her stood out more clearly than the rest, of something that had happened when they were watching TV together once. The reporter on-screen had been interviewing first graders about what dreams they had for the future. These children, about the same age as Minato, looked into the camera and said – embarrassedly, but with their eyes shining – that they wanted to be a professional footballer, or a patissier; or maybe florist, doctor, or zookeeper.

Minato had wanted to be an astronaut.

He'd wanted to float through the sea of stars, to feel for himself the grandeur of space. To stretch out his arms at the centre of everything, and know that the world was much, much more than his bed and his room. The words had slipped out of his mouth then – “No one asks me what I want to be when I grow up.”

Miss Fujiwara had stiffened; and then, when he turned to her, she was wearing an expression he'd never seen on her face before. “Sorry,” she had whispered, turning and running out of the room.

Her apology, he could tell, had been said through tears.

Why did she react like that? was a question Minato began to ask himself. Time, at least, he had aplenty for it. So he began to think, and his contemplations had led him spiralling ever and ever downward until it seemed to him that he must resign himself to reality. His future was clearly a topic that no one dared touched upon – could it be, perhaps, that it was because he didn’t have much of one? Whenever he’d ask about when he would be able to leave the hospital, Miss Fujiwara would always answer with a “Probably next week.” His calendar had already been marked with many such days that invariably had to be postponed to a later day and a later next week. Sometimes he'd say to himself that he wanted to go home, just to try out the feel of the words, but he didn't even have any idea what his home looked like.

So that was how it was, was it?

He was never to leave this place. Never to accomplish anything, forever to live out his days in a hospital room. Incapable of speaking like other children about professions, of dreaming like the others of a future.

He'd always considered himself to be in fairly good health, but maybe his sickness was more serious than he'd thought. He'd often felt that his sense of time was a little confused – was that because he'd been spending a lot of time anaesthetised and unconscious?

To have no future, and no hope for tomorrow.

That was how it was.

The truth was beginning to sink in now. For all that he lived in a hospital, he'd always considered himself just an ordinary boy. But he wasn't an ordinary boy, would not ever be let out of the hospital, never to attain any form of significance or meaning – would only ever to lie here, on this bed.

That was how it was.

There was a story that Minato had heard once – he couldn’t remember where – that had concerned a tree in the middle of a forest.

This tree had taken root in a place deep, deep inside the mountains, in a place where no human had ever trodden foot. The forest that it grew in was one bounding with life, inhabited by all kinds of animals that would scramble up and down the tree, make their homes in it, and eat its fruits. Squrrels darted through its branches; birds roosted; and not a single human being knew anything about it at all.

But the tree could not go on providing shelter for the inhabitants of the forest forever, and at last, inevitably, came the day when, with a great crraack! the tree fell, and hit the ground with the most momentous thunder ever heard in the region, the sound echoing long and lingeringly in the mountains.

And now came the crucial question: had any human being heard that noise?

Had an errant villager living on the foot of the mountains heard the noise and additionally recognised it as the sound of a tree falling, the villagers would have been able to infer from it that such a tree had existed. But what if no one had heard it? Then its existence, as far as people were concerned, was of no meaning at all.

It didn’t matter then how much the tree might have been loved by the animals of the forest, nor how strong and tall it might have grown – at the end, all because it had led a life apart from humanity, the tree was destined to pass away, unmarked and unknown.

I am the tree in the forest, thought Minato. My life began here and will end here, forever unknown to the world. In not being able to leave the hospital room, Minato’s very existence would become something with absolutely no meaning or worth. Worse – his would be a non-existence.

He would think this, and sigh.

It would mean that all the books he read and all the difficult TV programs he watched were nothing but tripe and self-satisfaction. He’d never be able to do anything meaningful for the world with it. He could become as smart as an encyclopaedia and no one would ever know if he couldn’t get out of the hospital. And even if he managed to create something amazing and furthermore, managed to spread it out to the world, he’d have no way of proving that it was he himself that had created it, and not an impersonator or even an AI.

He’d look up from his bed at the night sky. With the naked eye it was possible, if conditions were good, to see stars as faint as the sixth magnitude. But in reality, of course, the sky was filled with stars of up to the tenth, twentieth magnitudes, shining away. Shining away with all their might, without a hope of being seen.

He was the same as these stars, he knew.

The boy would strain his eyes until his temples began to hurt and his eyes began to hurt, seeking out these stars that could not be seen.

You're there, aren't you? he’d think.

I may not be able to see you, but you are there, surely.

I of all people would know that.

In the void that was the Big Dipper's ladle, in the void of Libra's scales, in the void held within Aquarius' pitcher, the boy sought furiously for himself. It became a nightly ritual to him. And as the days of its unbroken observance went by, and then the months, seasons and eventually years his sense of time began to disintegrate into a uniform blur, while overhead the constellations wheeled in their stately, imperturbable procession.

And then had come the meteor shower—

He had not been searching for it; rather, it had sought him out. A fierce torrent of light come to coruscate his entire being.

And if the light could reach him, then there were no obstructions between them. If the light could be seen by him, then he too could be seen by the light. His life that he'd thought shut up in here had in fact been noticed by the world outside.

What could that light have been? It was much, much too bright to have been a shooting star.

If it wasn’t just any ordinary star, he found himself idly wondering, then it might even be an portent of some sort. A sign that a miracle had happened – that he had been saved by the light. It had brought change to his life of endless, mindless repetition, and given his existence light.

You saw who I was. In the silence, with his eyes closed, Minato spoke to the now vanished meteors. You know that I'm here. Saying that, the boy sank back into a darkness of turbid, incoherent time.

His eyes felt light. It came piercing through his eyelids.

Another meteor shower, he thought; but this time seemed different. It had been so long since the meteor shower – it felt like a long time to him, at least. What was the light that had woken him now?

With his eyes still closed, Minato tried to remember what had happened before he'd fallen asleep. Dominoes rose, recollections resurfaced.

Yes. He'd been reading a book today. The book was a gift from his father, called Tales of the Constellations. Its author was a prolific writer on astronomy called Kusaka Akira[2], and Minato had found the book to be extremely fascinating. It had talked about the Greek myths, the foundation to so many constellations, which were filled to bursting with daring adventures and the doings of whimsical gods. Gods were supposed to be transcendental beings, forever concerning themselves with important things like the fate of the world, but in the Greek myths if the gods weren't off abducting women then they'd be busy scheming against each other out of jealousy, acting so flawedly and humanly Minato could not help but be amused.

The book had also talked about the stars themselves. There were some difficult parts, but many of its facts and descriptions he'd found extremely interesting: some, like how stars that looked close together in the sky could actually be separated by thousands of light years, or how stars weren't glowing rocks in space but balls of gas lit by nuclear fusion, were even new to him. Jupiter, it'd seemed, had been even just one step short of becoming a star like the sun.

Now the fog in his head was clearing. He'd been on the Jupiter page when Miss Fujiwara had come by. She’d lifted the book out of Minato’s grasp with slender fingers. He’d protested, “Hey…”

She responded with mock frown. “It’s time for lights out,” she said. “You don’t watch to catch another fever again, do you?”

But no. Had this really happened today? He could have sworn it had been the day before yesterday…

For an instant the boy was thrown, but he quickly found his footing again. It had been today.

“I'll be fine,” he answered. “It's because everyone makes such a big fuss about me that mom and dad get so worried.” He wondered, as he said this: how many times had Miss Fujiwara said that to him, and how many times had he given the same response?

“Well, you'll be discharged next week, so just put up with it a little longer.”

And these lines, too; how often had he heard them? You'll be discharged next week. You'll be discharged next week.

When Minato began to look mulish, Miss Fujiwara put on a slightly more serious expression. “Goodnight, Minato,” she said, her tone a little sad.

“Goodnight.”

Miss Fujiwara turned the lights off and left, and Minato gave a sigh, burrowing into his bed. As he pulled the covers right up over his mouth, the silence of the night drew coldly in around him.

He shut his eyes and imagined what it would be like if he were an astronaut. If he could go anywhere in the universe?

He'd head for Jupiter and try going right through the Red Spot. He'd call out to the constellation Cygnus by its former name of Leda, free Princess Andromeda from her chains, and then play with the great and lesser dogs and bears. He'd play hopscotch with the black holes and ride the waves of a super nova, before at last plunging headfirst into the Milky Way – and when he did so, surely a million million stars would rise like foam from the splash, and everything all around would be bedewed as if with diamonds…

Yes.

He'd been deep in this fantasy, and had before he knew it, fallen asleep. Until now, when the piercing light had woken him.

He opened his eyes sluggishly and looked out at his hospital room. The night light burned its familiar dim orange, and the night was cold and dark and unchanged—

No. There was something that had changed.

There was a light glowing at the foot of his bed. Minato had never seen fireflies before, but if he had, he would certainly have recognised the way the light grew and faded, exactly like a living creature drawing breath. Cautiously, he eased himself up. The bedsheets rustled loudly as he did, but the light showed no sign of vanishing. Moving slowly, Minato shifted the blankets off his body. His hair, grown long in his days of convalescence, moved lightly against his ears as he squinted hard at the light.

At that instant, the curtains at the window suddenly swelled with a great billow.

Minato found that he was shivering. Was it a draught? But the windows were always closed at night. But what was it, then? Surely not a ghost?

He gathered the sheets tightly around him, and at that moment, heard a voice.

“Oh, found it.”

It sounded rather pleased.

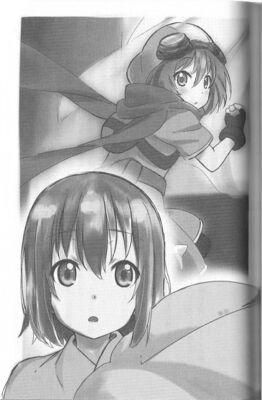

In through the curtains and the window ought to be have been closed dropped a boy with flying goggles over his eyes. He looked about the same age as Minato. He wore a hood that looked like a racing helmet on his head, a long scarf around his neck, and a short-sleeved jumpsuit, like something that might have been worn by explorers, with shorts that ballooned slightly about about the thighs. Most striking about his appearance, however, was a large, four-pointed star on his chest.

The boy approached the slowly twinkilng light with smart clicks of his boots. “I'm on a roll today,” he said to himself. And in a smooth motion he bent down and picked the glow up.

“What's that?,” asked Minato, breaking the silence. “Who're you?”

The boy jumped at Minato's voice, letting out a surprised yelp, and then slowly, nervously, turned around. “You can... see me?” he asked, his voice trembling a little.

Well of course he could see him, since he was standing right there; what was that supposed to mean?

The boy held up the light source and waved it at his right. Curious as to what the boy was doing, Minato's eyes were drawn to movements of the light. The boy waved the light at his left and and watched as Minato's eyes followed it.

“Hmmmm. Looks like you really can see me,” he said, massaging his brow like a grown-up. “How uncommon. How truly uncommon.” The lines of a hard-boiled detective, for all his explorer's clothes. With a world-weary sigh and a lift of his shoulders he hopped up onto the footboard of the bed, muttering remonstrations, and squatted there on the board like a frog. With his goggles up, his face, lit by the glow coming from his hands, was somewhat round, his eyes big and bright; were one to look only at his face he could certainly be mistaken for a girl. The star on his chest turned out to be something like a star-shaped clasp for the straps of his rucksack; this same star-like designs he also wore on both sides of his shorts, glinting dully. He grinned at Minato, who had drawn back from his sudden approach. “Well, how do I appear to you?”

What a strange question to ask. “How? Like a boy around my age, like me…” Minato trailed off with the realisation that he could not tell if this was really a boy.

The boy did not notice. Bending closer, he said, “But I do look cool, right?”

“Uh, I guess?”

“Give me a yes or a no!” he said. “I do look cool, right?!”

“Um, yes. Uh… cool.”

The boy hummed, looking satisfied. “Thank goodness for that,” he said. “You see, my appearance is created from your imagination. Basically, I reflect your inner thoughts. Wouldn't do if I ended looking bad, right?”

Question marks were now launching by the dozen in Minato's head following this bizarre string of events: Boy waltzes in through window supposed to be locked. Picks up mysterious glowing object. Acts like he should be invisible. Proceeds to verify that he looks cool? No, he wasn’t understanding what was happening at all.

Seeing Minato's blank look of incomprehension, the boy jumped down to Minato's side, sat, and leaned in with a wide grin. “I guess it can't be helped if you don't understand,” he said. “I am a first of a kind to this world. Being an alien.”

“An a-a-a—“

“Do calm down.”

“A-an alien!?” Minato's voice shot up an octave from sheer surprise. The tendons in his face twitched as he wavered between amazement and incredulous laughter.

“W-well, you certainly did show up under unusual circumstances, I suppose,” he said, fighting to stay rational. “Yeah, it wouldn’t make sense for any ordinary kid to sneak into a hospital, would it?”

“Now don't you call me a kid,” the boy said. “I'll have you know that in Earth time I'd be this—this—this much older than you!” Then, suddenly – “Oh! But don't start thinking of me as an older person, I'd rather not lose the look I have now.” In perhaps direct contradiction to his words, however, he was flapping his two arms about in a tizzy and generally not acting very old. Without quite meaning to, Minato began to smile.

The boy took the smile to be one directed against him and began to sulk. “Well, fine if you don't want to believe me. But at least accept that my coming here and being seen by you was not a coincidence, but fate.”

“Fate?”

The boy twisted around until he was looking directly at Minato. “Tell me,” he said. “Have you seen a star?”

A star. Minato remembered.

“Oh, yeah. Some time ago… though I’ve lost count of the days since then. But I saw them, so many and bright I thought I must have been dreaming.”

“I knew it.” The boy leaned back to look at the ceiling, kicking his heels. “You had the capacity to see it. Your fate must have been bound up with mine at that moment.”

“But,” protested Minato, “what exactly do you mean when you say 'fate'?”

“Hmm.” The boy tilted his head further back at this question. “What I wanted to say was that your future was crossed with mine. Something along the lines of us being destined to meet. By that I mean – well, in human terms, it'd be like going into a park and having a ball fly right into your face, and coming to be friends with the ball's owner because of that. That sort of fateful encounter.”

“I don’t have any friends, so you’ll have to find a better analogy,” answered Minato automatically, before he could stop himself.

“Oh?”

Minato saw a glimmer of sympathy light up in the boy's eyes, and added hurriedly, “But I do understand what you're saying. That we're able to influence the course of each other's future.”

“You’re a bright one to understand it so quickly,” said the boy. “I wonder why, then…” He fell into thought, murmuring, “Uncommon, indeed uncommon.”

“What's uncommon?” Minato asked.

“That a human as old as you can see me - that you still have that innocence. The stars must shine on still in your heart. Even so, to be drawn so to you….” Suddenly his eyebrows shot up. “Goodness,” he said, turning away. “I need to go.”

“Wait!” Minato reached out and caught hold of Elnath's scarf just as he was lifting off and yanking him back onto the bed, making strangled-sounding noises. “S-sorry,” Minato said, hurriedly letting go.

“Could you humans be any more violent?” Elnath cried.

“Sorry,” said Minato impatiently. “But look, you said that we were bound together by fate, right? So tell me everything. What's that light in your hand? And what's so uncommon about me?”

“Some things are better left unknown.”

“Mysteries exist to be solved,” said Minato firmly. “Tell me!”

“I'm just thinking of your own good—ow! Stop! Stop!” Minato had taken hold of his scarf and was pulling on it hard.

“Tell me!”

“I will, I will! Now let go, let go, let go—“ Minato let go and the boy fell to his feet, gulping at the air wildly. At length he croaked, “What a fascinating place I've come to. Is this also fate at work?” He set his scarf painfully to rights and sank cross-legged onto the bed—

“Shoes off.”

“Yes,” said the boy meekly.

It was all so very honest. Minato had never spent any real time with another person of his age, much less have fun doing it, constantly surrounded as he had been by grown-ups. Now he was having to learn, even in this very moment, how to hold back his laughter.

The boy fiddled somewhat aimlessly with the goggles on his head. “Where to begin,” he muttered, then making up his mind and saying, “You said that you saw the meteor shower here, right?”

“Yes.”

“Well, what you saw was an explosion on our spaceship. A part broke off in the explosion and fell onto your planet, breaking into pieces as they went. So the engine became broke, and our energy even began to leak away…”

Minato drew in a sharp breath.

The boy was continuing on. “Normally, because our ship exists both as mass and energy at the same time, in a state of quantum superposition, it isn’t visible to you humans.” He stopped, noticing how furiously Minato was blinking from incomprehension, and sighed. “This is a difficult concept to get. Did you know that light can have the characteristics of both a particle and a wave?”

Minato hesitated a moment before answering, “Kind of. I've heard of it.” Even though he knew a lot more than most children his age from his books and TV programs, quantum physics was still a area of science he was more than happy to pass over whenever possible. He knew, at least, that light was made up of photons. In trying to explain the photoelectric effect, Einstein had come to the conclusion that that had to be the case. However, it was also well accepted at that time that light was a wave, as light shone through two thin slits close together would cross itself to form an interference pattern. What this seemed to mean was that light possessed properties of both a particle and a wave. In the due course of time it would be discovered that photons were not alone in such behaviour, but that electrons, protons, neutrons and other particles all shared this same characteristic of duality of behaviour.

The alien boy’s explanation continued on, heedless of whether Minato was following: “When light behaves like a particle, it becomes possible to determine its position with certainty; yet at the same time, precisely because it is a particle, its wavelength becomes undecided and capable of varying wildly, and its momentum becomes indeterminable. On the other hand, when monitoring a wave, while it is possible to observe a wave as it propagates through a medium, doing so fixes its state and makes it impossible to ascertain the position of the particle of the wave.”

“S-slow down,” stammered Minato, floundering in this wave of information. Newtonian physics, at least, he could understand, as it dealt with the workings of physical, tangible objects, but the particle physics that they were now dealing with was a different beast altogether, a physics of the unseeable and the untouchable, where the truth often proved stranger than the fiction. Yes, indeed, it was certainly possible for a large number of particles to move in a general wave-like motion; to say that the particle itself was the wave, however, required a little feat of the imagination.

“It doesn’t make sense, does it?” said the boy, looking down with a faint smile. “Well, of course it doesn’t. This sort of thing would sound like magic to any ordinary person.”

“A magic ship,” said Minato.

The boy stared surprised at him, then broke into laughter. “I like that!” he said. “Yup. Let’s just say that it was all magic.”

Minato let out a sigh of relief. The difficult explanations, it seemed, were over. Pointing at the boy's hand he asked, “Is that thing also magic, then?”

“Do you know what crystallised potential is?” answered the boy. “Because that’s what this thing is.”

“Crystallised… potential?” repeated Minato, not understanding. He knew what the word potential meant, and likewise what crystals were. But potential was something abstract and intangible: how could something like it possibly form crystals?

“You up for an explanation?” Elnath said, not unkindly.

Not another incomprehensible explanation! Minato thought, his throat tightening up. And yet in the next instant he found himself nodding. Curiousity was without a doubt a part of it. But more than that, he was yearning for an opportunity to continue being with someone of his age, within whom he could hold a proper conversation. What kind of person this someone was didn’t really matter, nor the actual subject of their conversation, not even when it was theories and ideas that far surpassed his comprehension; not when they sat so close to one another they could practically feel each other’s breaths, could look up to see the other smiling, and smile back in return. This was how healthy kids got to spend time with their friends! Who could have known that it would be so, so fun?

He made a determined face, which the alien boy took to be a sign of acceptance.

“Very well. I’ll try and keep things simply on my end,” he said, much to Minato’s pleasure. “Right. Let’s see.” He tapped at his cheek in thought for a moment, before finally opening his mouth.

“You have two kinds of debris coming off the explosion on our ship,” he said. “The first kind are engine fragments, extremely important pieces of the ship’s engine that I would be collecting if I had the power to do so right now. And the second kind is this crystal that I have here, a type of fragment that we use as the energy source of our ship.

“So why is it called a potential crystal?”

The boy turned both of his hands face-up and moved them alternately, like a pair of scales. “They can be matter, or they can be energy—” and here he brought his hands so that they crossed each other, not, and then again, in a oscillating gesture. “Until an observer focuses on one particular property, they're neither matter nor energy. They exist in what is called a superposition of states. A better way of putting it would be so say that they have the undecided potential to be both these states.”

“Yes…”

“And it so happens that humans are not unlike our ship, in that respect. The way fate works for them, see, is quite similar as well.”

Now what? thought Minato. Did he really have to throw a concept as heavy as fate on top of this already confusing explanation? But Elnath was going on.

“The younger humans are, the more they are not anything. They waver between their possibilities, you see? These fragments of potential bear a strong affinity for such people that aren't yet anything, and get drawn into them.”

A faint “Oh.” was all Minato could manage for an answer.

The boy was making wild gestures as he spoke now. “Small children exist in the midst of a whirl of possibilities, don’t they? They’re never sure of what they should do. Maybe they're told to become a doctor when they grow up, but really they want to be nursery school teacher – but also maybe a musician, or maybe a football star. The fragments delight in such uncertainties. And these uncertainties don't just have to be about when they grow up. Maybe they're thinking that they want to eat ice-cream, but ramen seems nice too – oh, but no, tonkatsu's what they’re feeling like today, you know? I mean, I haven’t tried it before, but I can just imagine how tasty that golden, tender piece of meat must be...ah.” The boy came to a halt, realising that he’d been licking his lips and rubbing his hands together in an altogether unseemly manner. When he spoke again it was to be with an edge of hurried embarrassment.

“A-anyway. Whenever such a child decides on an action, a potential crystal is released. Ejected from its safety in the ambiguity within the child, you might say. From something that was neither matter nor energy, they eventually will become fixed into one of the either of these states that they’ll become.”

“And is that a good thing or a bad thing?” asked Minato uncertainly, his voice small. He'd thought that making choices was a good thing. But the boy had spoken of indecisiveness as 'safety', as if it were a good state to be in.

The boy snorted huffily through his nostrils. “That depends on the person. On what they make of their own destiny.”

“Huh,” said Minato. “And what about the released crystal?”

“It disappears.”

“It disappears?”

“Well, once it gets decided and fixed into a certainty it no longer serves any more use,” the boy said. “Holding on to it would be like a snake holding on to its shed skin.”

“But that's just kind of sad, isn't it?” said Minato. “Even indecision can be an important part of a person's life.”

“Yes,” answered the boy, “but that also depends on the person. Some people like to look back on the lessons they learned while coming to a decision. Others just want move on and forget about all the time they wasted coming to a decision.”

“So what do you do with this waste once you've collected it?” asked Minato.

The boy made a face at Minato calling it “waste”. Well, he was the one who'd called it that first. “I never said that it was completely useless,” the boy said. “With our technology it's possible to consume these unfulfilled futures and all possible events that could have led up to them as a source of energy. We can use the crystals to repair our ship.” As he said this he undid the star-shaped clasp on his chest and let his backpack down. From within he pulled out a drawstring pouch, which he opened and emptied onto the bed. Seeing the contents of the bag, Minato gave a cry of admiration.

They resembled pieces of rock sugar, glittering in all the colours of the rainbow. No other words could fairly depict the sight of those beautiful crystals.

There were crystals of red, crystals of blue, crystals of every colour imaginable, all of them bearing marvellously complex exteriors that caught the light and reflected it in fascinating ways. Certain of the crystals among them, of not insignificant size, were even possesed of the ability to alter their own colour by gradations, much like variable stars in distant space were known to do.

To this pile added the boy his recently acquired crystal of not too many minutes before. The crystal bore dissimilarities to all the others in that its shape was one of a smooth sphere, glimmering dully with a silver sheen rather than glowing; its very center seemed to be composed of a solid, congealed material.

“Indeed uncommon,” the boy pronounced. “You truly are a—”

But at this instant he knitted his lips shut and would not continue. “I must leave now,” he said; “I can't spend all day dilly-dallying with you here;” scooped the crystals up to stuff them into his bag, and turned to leave.

As might be expected, Minato caught hold of the boy's here. He yanked! As on a fishing pole, the boy described a great and elegant arc in the air before falling on his back upon the back, the impact eliciting from him a squawk of surprise.

“What more could you want of me?” came the boy's weak, helpless expiration, his large, luminous eyes swimming in an exquisite picture of abjection. “The reason for your uncommonness? Let me tell you, I absolutely—”

“Let—let me help!”

Cried Minato, with all the force in his person.

“I want to help collect your potential crystals!”

In the meantime his fists had clenched themselves at his chest, his shoulders were heaving and his cheeks had become hot and flushed. Such a sheer fervour of excitement was something he’d never experienced before.

The boy regarded Minato with some surprise. “Well, certainly, you'd be capable…” he said, then suddenly, “No, that wouldn't—”

“Please!”

Taken aback, the boy cast his gaze around the room. At the constellation chart, at the astronomy books, the telescope, the miniature planetarium, the lightless TV.

“Aren’t you supposed to be resting, though?” he said.

“I'm fine!”

The boy folded his arms and looked downwards, a little philosopher in thought. “Hmm,” he said. “Well. I am sort of stuck if my ship doesn’t get repaired. Might as well follow this path to the very end, right? I’ve been walking on it from the very moment we met.

And even as Minato's face lit up with delight, the boy snapped his fingers. Immediately a sensation of his very body melting away into the air assailed him – he gaped, exclaiming a started “Hueh?” – and the next instant the transformation was over. The pyjama-clad boy now carried a sceptre in his hand, the sceptre’s head a cresent moon around a star. The pyjamas were gone, too, and in their place was a coat cut from a cloth of the purest white, with golden stars at the lapels. At his throat sat a big, red bowtie, with a golden star equal in size to the alien boy’s clasp at the center of the bow, fixing it into place. Frills lined the cuffs of his sleeves; and white calf-high socks, suspenders and shorts completed the lower half of his outfit. In fact the entire outfit was the sort of thing he’d always dreamed of wearing, it being the sort of thing only healthy kids got a chance to wear.

He turned to look at his reflection in the window; immediately blushed out of shyness at his appearance. There was a high collar covering his neck, and epaulettes on his shoulders, and was that a little crown sitting on the top of his head?

“I look like I’m supposed to be a prince[3] or something,” he said, not quite daring to believe his eyes. The pallor of his illness gave him the appearance of a sheltered noble; when he reached up to brush his long hair back he could even see a pair of small, star-shaped earrings on his ears.

He stood up on the bed and did a quick whirl. The ends of his coat flared out; the lanyard dangling from his right epaulette flared out; the wind moved through his hair; his earrings, carried by their inertia, bumped him gently on the face; never before had he felt so light and free. He felt giddy at his newfound freedom. Just as going out on a hunt for potential crystals would no longer pose a problem for him, he knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that everything he’d ever dreamed of being able to do would now be doable for him.

“I took it from your imagination. You've got pretty good taste, you have,” said the boy cheerily.

Minato, lifting the hem of his coat a little, asked,

“How do I look?”

“Very cool.”

Quite possibly this was the highest praise to the boy. Minato felt an unfamiliar warmth in his heart, and could hardly hold back a wide, silly grin at the compliment.

“Well,” said the alien. “We do have a problem to deal with before we get going, though.”

“What problem?”

The boy quirked his lips. “I still don't know your name. I can't just call you 'Hey', can I?”

“Minato,” Minato said, “My name is Minato. And yours?”

“Ah, about that….” The boy’s eyes slid away from Minato’s. “Do you think you could do me the favour of giving me one? You were the one who gave me this wonderful look of mine, so it seems only fair that you give to choose a name for me too.”

“Really?”

“I won't take any names that aren't cool though,” the boy added.

Minato gave an determined nod and set about thinking up a name. He came up with a blank.

Now Minato was forced to admit to himself that there really was nothing at all cool about the boy’s appearance, which, with its combination of puffy shorts and an explorer-themed costume, made him look, well, cute, if anything. He would have to look for inspiration elsewhere. And so Minato cast around for other ideas – stars… constellations… meteor showers… aliens….

“That light came from the direction of Taurus, didn't it?” he said, struck by a thought. He picked up the book on his drawer – Tales of the Constellations – and began to leaf through it. “How about Elnath? It's another name for Beta Taurus.” He pointed it out to the boy, who frowned a little uncertainly.

“Why not Aldebaran, for Alpha Taurus?” the boy said. “Are you keeping that for yourself?”

“Well, Aldebaran’s kind of long, isn’t it?” said Minato. “And it doesn’t really suit you anyway. And um, well, I was thinking… wouldn’t it be nice? Elnath and Minato sound kind of similar, you see….”[4]

“Ahh,” said the boy. “As a sign of us being partners, you mean?”

Now it was Minato's turn to frown uncertainly. He himself hadn't actually thought as far as anything so official-like as partners – all he'd wanted was to have something that he could share with the boy, purely as friends. A little belatedly, he began to wonder if the boy might object to having such a wish be forced onto him…

The boy in question was grinning from ear to ear. “I like it,” he said, and Minato breathed a sigh of relief. Minato and Elnath. Elnath and Minato. It seemed like they would become good partners and good friends.

Elnath pulled himself up. “Well, time to go, Minato.”

“Right now?”

“Of course.”

“But it’s already this late,” said Minato with some surprise. “Will we be able to make it back by morning? If they find that I’m gone there’ll be a huge fuss afterwards.”

Elnath looked at him silently for a moment. “Time, for your people,” he said softly and clearly, “is linear and unidirectional. But not for me, and not for you anymore either.”

Minato didn’t understand, but by this point Elnath had already turned to throw open the window, without so much as a word of explanation. He stood with one leg braced on the window frame—

“Let's go.”

—a hand stretched out towards Minato. Now he was the one who looked like a prince.

Minato gaped. “That's a window,” he said.

Elnath took firm hold of Minato’s nervously outstretched hand. “What if it is?”

And then he leapt, cheerily as his words, out of the window. Minato cried out: “Wa—

Suddenly the night sky approached at great speed.

Before his eyes were stars, stars, stars. Reaching over him from one end of the sky to the other, the long Milky Way. And the light was no paltry glow, no ward-room bulb, but the light of a vast, endless universe.

And Minato was flying. The night breeze caressed his cheek gently, ruffling his clothes and hair. Up ahead was Elnath, puffy pants flapping as he flew. Turning, goggles over eyes and a hand holding down his hood, he grinned at Minato. “Good, isn't it?”

Minato looked down. The city beneath seemed like model town, now. Houses became tiny pinpricks of light; motorcycles drew red trails with their tail-lamps. His heart felt as though it would leap out of his mouth. His blood pounded like it was ready, any minute, to blow. He was filled with so much amazement that he feared it would spill out and over.

I've managed to escape, Minato thought. From entrapment, from loneliness. From even the gravity that holds everyone on the planet in place. He felt as though a minty fragrance was spreading through his chest, as though his field of vision was widening, as though Ode to Joy was playing by his ear. He wanted to shout out to the whole world: He was the prince! Nothing was impossible for him! Everything was possible.

“Let's go find those potential crystals, Minato.”

It was like a summons, from the magician to the chosen prince. Minato had never before been so pleased to hear his name.